Remembering Perry Brickman

The Tam Institute for Jewish Studies mourns the loss of Dr. Stanley “Perry” Brickman, a long-time friend and supporter of the Institute, who passed away in Atlanta on Jan. 26, 2025 at age 92. A beloved leader in the Atlanta Jewish community, Perry received international recognition over the past two decades for his courageous work uncovering and documenting the story of antisemitism in the former Emory University School of Dentistry, where he was among the many Jewish students who were dismissed unfairly during the years 1948-1961. Perry’s work ultimately led to a formal apology for this discrimination by Emory’s President James Wagner in 2012.

A native of Chattanooga, Tennessee, Perry first came to Atlanta in 1949 to attend Emory College. After completing two years of undergraduate work, he was eligible to apply to Emory’s School of Dentistry, where he was accepted as a student in 1951. His admittance to the Dental School occurred three years after the arrival of the School’s new dean, John E. Buhler, who, during his thirteen-year tenure at Emory, carried out a systematic campaign against Jewish students in his division. Although Buhler did not have the ability to restrict the inflow of Jewish students into the Dental School, which was controlled by a university-wide admissions committee, he used his power as dean to consistently flunk out Jewish students or force them to repeat one or more years of their dental education.

Like a number of other Jewish dental students at Emory during this period, Perry received a letter at the end of his first year informing him that he had failed and would have to leave the school, despite his strong grade point average. Perry had always been a strong student and never imagined he could be subject to dismissal on academic grounds. In dismissing Jewish students, however, Buhler often tried to neutralize the strength of their academic performance by arguing that Jews “didn’t have it in the hands”— that they suffered from deficiencies in the manual dexterity necessary for the practice of dentistry. The shock and embarrassment Perry felt upon receiving Buhler’s letter was compounded by the need to explain the dismissal to his parents, who had worked hard to put him through school so that he could realize the educational opportunities that had been unavailable to them in their youth.

Perry successfully transferred to the University of Tennessee and, despite the setback presented by his Emory years, went on to graduate with a B.A. in Biology in 1953 and a D.D.S. degree in 1956. At Tennessee, he received honors for his academic work, including election to the Dean’s Odontological Society. Immediately following graduation, he served two years in the U.S. Air Force Dental Corps and, after completing training as an oral surgeon, he settled in Atlanta in 1960 and opened a private practice in Decatur. He had decided to return to Atlanta because it not only offered opportunity for a young surgeon, but also because it was the hometown of his wife, the former Shirley Berkowitz, whom he had met during his undergraduate years at Emory.

Brickman’s return to Atlanta marked the beginning of a successful professional career spanning more than five decades, during which time he rose to become one of the region’s most respected practitioners in his field of specialization, oral and maxillofacial surgery. He also made his mark through philanthropic activity and community service. He regularly offered his services free of charge to low-income residents of Atlanta at the Ben Massell Dental Clinic and extended free or reduced-price dental care to needy patients at his own Decatur practice. Perry also became a towering figure in the associational life of Atlanta’s Jewish community, serving over his long career as a trustee of no less than a dozen different charitable and communal organizations. From 1990-1992, he served as the president of the Atlanta Jewish Federation, the Jewish community’s central organizing and philanthropic agency, and subsequently served as a trustee for life.

At the time of Perry’s departure from the Emory School of Dentistry, he was not fully aware that his dismissal was part of a much larger, systematic process of discrimination against Jewish students. Over the years, he discovered other Jewish colleagues in the dental field who confided in him that they had also experienced discrimination at Emory. In 1961, rumors of Buhler’s antisemitic practices finally sparked an investigation by the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) and Buhler resigned, but Emory did not acknowledge that Buhler was fired for cause or that any anti-Jewish discrimination had occurred. Although Buhler’s administration had ended, the Jewish men he had unfairly dismissed remained reluctant to speak about their experience. Still traumatized by the embarrassment of having received failing grades or having been dismissed from school altogether, and because Emory never acknowledged any wrongdoing, these former students often continued to conceal the story of their Emory years from friends, associates, and in some cases even their wives and children, creating what Brickman’s wife Shirley later termed “a fraternity of silence.”

In 2006, however, as a result of an exhibit on Jewish life at Emory staged by the Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library (MARBL, now the Rose Library) of Emory’s Woodruff Library, Brickman began to think about revisiting his time at the Emory Dental School and researching more deeply the larger story of what had happened to him and other Jewish students during John Buhler’s tenure. The exhibit, which I curated in my role as a Jewish studies and history professor on campus, included a section about the Dental School episode, reproducing a chart from the 1961 ADL inquiry showing that a staggering 65% of all Jewish dental students were affected by discriminatory practices during Buhler’s tenure as dean. Perry was encouraged by the exhibit’s public airing of this information, which was the first time it had been acknowledged in any meaningful way by Emory. In a series of subsequent discussions with Perry, I told him that I thought the Emory administration might be ready to officially acknowledge and confront this painful episode in its past, just as they had recently issued an apology for the institution’s involvement in slavery in the years before the Civil War.

While mulling over this idea, Perry decided to delve into his own research on the former School of Dentistry’s discriminatory practices (the school had closed permanently in 1992). Perry tracked down a host of archival sources that added much more detail to our knowledge of the Buhler years. Most significantly, however, he tracked down the victims of Buhler’s policies, many of whom broke their silence for the first time when Perry asked to record them on videotape. Perhaps the most important aspect of Perry’s research, these oral interviews uncovered the human side of the story—the ways in which this discrimination shaped individual lives, career trajectories, and family dynamics—a dimension that had been missing from the ADL’s study, which was based only on statistics and purposefully avoided mentioning any individuals in order to protect the anonymity of students who, at that time, were still struggling to land on their feet after leaving Emory.

After six years of research, Perry weaved the documents he had collected and the interviews he had conducted into a compelling video presentation, which told the complete story of antisemitism in the Emory School of Dentistry for the first time. I encouraged him to share this with Emory officials, and with Perry’s agreement, I arranged a meeting with Provost Earl Lewis, who viewed the video presentation in advance and gave his strong support to the idea of seeking an apology from the administration. Provost Lewis then put us in touch with Gary Hauk, deputy to University President James Wagner. Considering that Gary was also Emory’s historian, he was particularly interested in and moved by Perry’s research. He embraced the idea of an official apology, and also suggested that the university should go further than this by undertaking a project that would promote awareness of this painful history and use it as a means of education and healing. He suggested that David Hughes Duke, a documentarian who had collaborated with Emory on other projects, work with us to produce a professional documentary film, featuring Perry’s interview footage and research, and also adding in framing commentary from scholars, Jewish community professionals, and Perry himself.

Our meeting with Gary Hauk resulted in an historic evening on the Emory campus on October 10, 2012. Attended by over 600 students, faculty, and community members, the program featured both a public apology from President Wagner and a screening of the completed documentary film, From Silence to Recognition: Confronting Discrimination in Emory’s Dental School History. Due to Perry’s efforts, almost all of the living Jewish former dental students attended the event; they were personally received by President Wagner preceding the ceremony, and then had the opportunity to hear his expression of regret for the discrimination they suffered, which he declared to be inconsistent with values for which the university should strive. The impact of the event was felt not only on campus and in Atlanta, but also throughout the country and even internationally. The extensive press coverage of the event by the New York Times, CNN, the Washington Post, Ha’aretz, and other major media outlets, reflects how the powerful moral lessons the story evoked, and the historic nature of Emory’s confrontation with its past that Perry set into motion, touched and mobilized people around the globe.

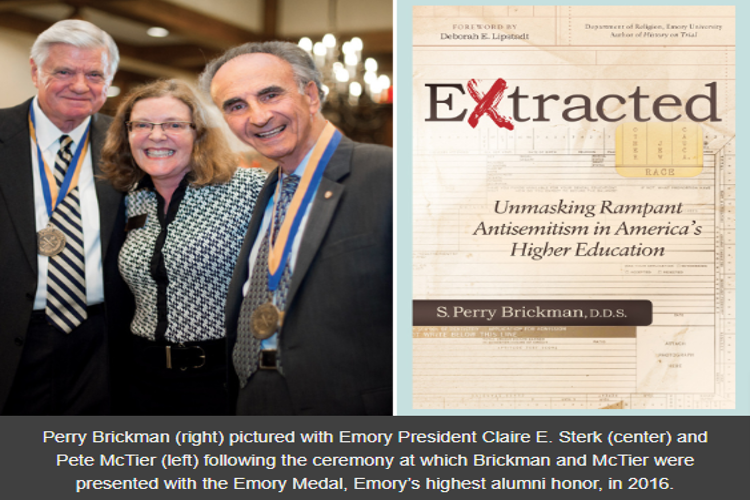

Perry’s research did not stop with this landmark event; he went on to further research the Dental School episode and place it within the larger national context of antisemitism in institutions of higher learning during the 20th century. The result was his 2019 book, Extracted: Unmasking Rampant Antisemitism in America’s Higher Education. Perry also became a frequent speaker at schools and organizations across the country, sharing his research, his personal story, and his journey of reconciliation with Emory so that others might learn from them. Perry’s historic role also continued to be recognized at Emory: in 2012, he received the “Emory History Makers” Award, and, in 2016, the Emory Medal, which is the highest Emory alumni award for service and philanthropy. He was also honored with the creation of the Brickman-Levin Fund, named both for Perry and Arthur Levin, the ADL regional director who Perry credits with gathering the evidence that likely led to Buhler’s departure in 1961. The fund, which is a joint effort of the Tam Institute for Jewish Studies and the Laney Graduate School, provides fellowship support for promising Jewish Studies graduate students, insuring that the study of Jewish life and culture remain a vital part of the Emory curriculum.

On a personal note, it was the honor of a lifetime to work with Perry, to watch his groundbreaking research as it unfolded, and to be a witness to his brave battle against silence and toward healing, reconciliation, and the recognition of historic wrongs.

The entire Tam Institute community sends its heartfelt condolences to Perry’s wife, Shirley, his children Lori, Jeff, and Teresa, and to his entire family. His loss is felt far and wide. May his memory be a blessing!

To view Perry’s obituary, and for information on where to make a memorial contribution, click here.

Published 2/13/15