Udel and Duke discuss Honey on the Page

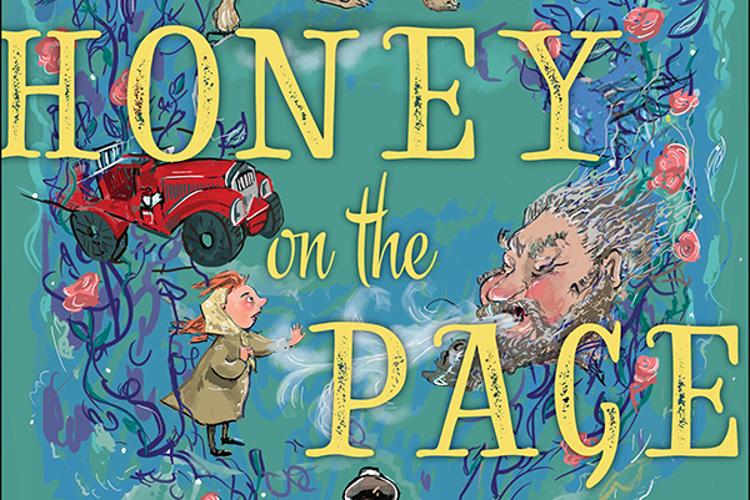

On Tuesday, October 20, 2020, the Tam Institute for Jewish Studies held a virtual celebration for the release of Professor Miriam Udel’s new book, Honey on the Page: A Treasury of Yiddish Children’s Literature. Professor Udel was joined by Professor Marshall Duke, Charles Howard Candler Professor of Psychology. In front of a virtual audience, TIJS Director Eric Goldstein introduced Professor Udel’s book both as a scholarly achievement that will advance the academic field of Yiddish studies, as well as an accessible cultural resource for families and children, for whom it will provide a key to the riches of Yiddish literature.

Professor Duke was asked to interview Udel for the occasion, as his own work has focused on a variety of family issues, among which are the importance of family stories and rituals in the nurturing of resilience and children. Because of their mutual interest in children and storytelling, Duke and Udel, along with another colleague, Professor Melvin Konner, collaborated on a project through Emory’s Interdisciplinary Faculty Fellowship program several years ago. As an outgrowth of that project, Udel and Duke co-taught a course at Emory that examined Jewish children's literature through various disciplinary lenses.

Professor Duke first inquired about the title of the book, which refers to the custom of smearing honey on a student’s primer. “Students as young as four or five, in some places even three, would come [to class] and in order to make the beginning of learning sweet, the melamed (teacher) would smear honey on the page, and the child would lick it up, symbolically incorporating that sweetness into the learning process. I wanted to put that Yiddish honey on the page,” Udel responded.

The two then explored the re-emergence of the popularity of the Yiddish language. Udel noted that while there are approximately 500,000-700,000 people, many of them Hasidic Jews, who use Yiddish as a primary language today, “there is absolutely a renaissance underway” among non-native speakers. Udel cited an “all-digital Yiddish journal called In Geveb, which now publishes a roundup of that year’s summer Yiddish programs.” Organizations such as the National Yiddish Book Center in Amherst, Massachusetts, and the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York offer intensive language programs in Yiddish, as do several institutions abroad. Udel also credits the arts, such as theatrical productions, music, and the visual arts, for a resurgence of interest in the Yiddish language.

“There’s a sense among many different kinds of people that Yiddish is a portable homeland, and that it is a way of connecting with Jewishness and the larger Jewish narrative,” Prof. Udel explained.

Duke asked why she had decided to translate not only children’s stories, but children’s stories from this specific period in history. The Honey on the Page anthology spans the Yiddish-speaking world from the 1910’s all the way into the 1970’s.

Udel responded by recounting the historical context behind the rise of the Yiddish children’s story, which she described as two-pronged. Due to the stratification of learning in Eastern European Jewish culture by sex, elite men would learn Hebrew and Aramaic and occupy their time with Talmud study and the development of Jewish law. “If you were female, or you were one of what they called the ‘men who were like women,’ in the sense that they had not had access to this elite education, then you might read simpler texts that were written in Yiddish, such as storybooks,” Udel noted.

“It was a later development that there was a concerted effort to create a literature, a set of texts, that would address children specifically,” she continued. “Because there was a wide range of ideological commitments . . . from what we might call ‘just Yiddish,’ to socialist-oriented Zionism, to Bundism, to full-fledged communism, and each of these ideological stripes had a political party associated with it, each of these political parties eventually came to have a network of schools, and those schools required reading materials. So, that’s one of the engines that’s pushing the development of this literature.”

The second engine was fueled by Yiddish cultural leaders who began to see the necessity of encouraging children to preserve the Yiddish language and to pass their own views to the next generation, which became a concern as a growing number of Jews integrated into local linguistic cultures in both Eastern Europe and the United States during the 1920s and 1930s. Due to the efforts of these leaders, “this literature starts to burgeon with the founding of multiple publishing houses, again associated with these political parties and their school systems, and by 1935 it’s absolutely galloping,” Udel said. The production of Yiddish literature came to an abrupt halt with the advent of World War II and the Holocaust. But, “in the 1950’s we see a real efflorescence, as children’s literature reconstitutes itself as a force for cultural preservation and consolidation of what it means to be Jewish after the Holocaust, going into the 1970’s.”

Duke asked Udel about the “bisemic” nature of Yiddish children’s literature, referring to the fact that many of the works in this genre “were for both children and adults. . . A child might read a story and get one thing, but the adult reading the story to the child gets something very different.” Udel credited this to the fact that many of the authors did not exclusively write for children. “[Borrowing a] phrase of somebody talking about American children's literature, ‘majors wrote for minors,’ meaning the most highly cultured literary practitioners would often try their hand at writing for children.”

Professor Udel also announced the beginning of a collaboration with Theater Emory and one of her former students, Jake Krakovsky, to create a puppet show based on the popular “Labzik” stories.

A question and answer portion concluded the webinar, which included questions about the origin of the Chelm stories, how Udel dealt with stories that might have been considered “too shocking” for modern readers, and the gender disparity among authors of Yiddish children’s literature.

Published October 26, 2020